Against Taste

Taste arrived quietly, somewhere over the last few months. It arrived the way a new technology consensus always arrives. It wasn’t argued into place. It simply appeared there one morning, like the weather.

No one proposed it. No one even had to. It was a clean and easy answer to the question everyone in technology has been asking: what are humans for once the models get good enough?

Taste was a clean and easy answer. It could be deployed at deliberative catch up coffees in San Francisco matcha bars, the kind with overstuffed croissants that end up on viral TikToks and hashtag-food Slack channels featuring sober coworker chat about slop bowls. And taste arrived at boozy New York allocator dinners where people counted their carry and felt bad about it while deploying it into Gin Lane houses and Park Avenue condos while discussed which venture capitalist got divorced that week.

Taste, of course, was the only thing that mattered. The ability to select, the ability to curate. The thing humans have been doing forever. Taste was an easy answer.

Taste comes to the party wearing Yohji Yamamoto pants and an OpenAI commercial-leadership-offsite Patagonia quarter-zip. Taste does drink, just a bit and sometimes more than a bit on weekends, but it does have a shockingly high VO2. Taste is a complete vision of what post-scarcity protein-heavy brunch looks like: shiny Accutane-and-GHK skin, emotions muted by insulin inhibitors and novel neurotoxic research chemicals.

I hate Taste.

Not because taste isn’t real. Taste is very real. I hate it because what we’re calling taste is a very dangerous and slippery thing. And when you look at what came before taste, you realize that what the taste thesis actually proposes is not an empowerment of human agency but a fundamental demotion. It might be the most elegant and well-branded demotion in the history of human self-regard. Consider what the word actually means.

For most of human history there was no concept of taste as we understand it. There was patronage.

Patronage was anything but taste. Patronage was a relationship between capital and artistic labor so intimate that the two were functionally a single body. The patron did not select from finished works on a wall, allocating neat sums of money to purchase them. The patron animated the work before it existed.

“The LORD God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to dress it and to keep it.” Genesis 2:15

The first vocation in Scripture is not to sit atop creation and admire its beauty. It is labor. Co-creation. Man’s original calling is to tend, to make, to participate in the ongoing work of creation. The garden is not a tasteful Japandi department store, finished so that software engineers can walk through it and tithe their income to its best elements. It is a living thing that requires redemptive labor.

The taste thesis, at its deepest and most simple structure, reverses this order. It places man at the end of the chain of creation, evaluating what has already been generated, rather than at the beginning, participating in the generation itself. It makes man what he has been slowly becoming for a century: a critic of creation rather than a co-creator. A consumer at his core.

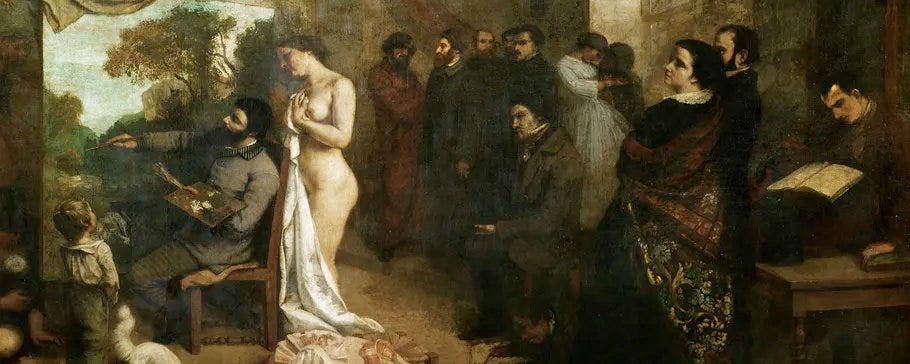

The bottega system, first pioneered in Florence in the fifteenth century, animated some of the greatest works humanity has ever produced. A bottega was not an artist’s studio in any modern sense. It was not a private room where a thoughtful artist communed with his own genius and waited for the muse. It was a commercial enterprise that took commissions. Verrocchio’s bottega, where the young Leonardo trained, was exactly this kind of place.

The patron didn’t stroll in once the painting was finished to evaluate it. He arrived before the first brushstroke. He specified the subject. He specified the materials. The contract was explicit down to the gram — how much ultramarine, how much gold leaf — because these things cost real money and the patron was not interested in artistic ambiguity. He specified the dimensions, he specified what figures should appear and where.

The painter pushed back. He knew things the patron did not. He understood composition, perspective, the play of light, the behavior of pigment on gesso, the structural properties of the poplar panels he would paint on. The patron’s money bought the ultramarine and the painter’s knowledge determined what it could become.

The negotiation between these two was the generative act. The patron’s capital and ambition, the painter’s skill and stubbornness. They were locked in a generative argument about what the thing should be, and what emerged was a product of that argument — not of anyone’s judgment, but of their shared labor.

This is how artistic creation worked for most of human history.

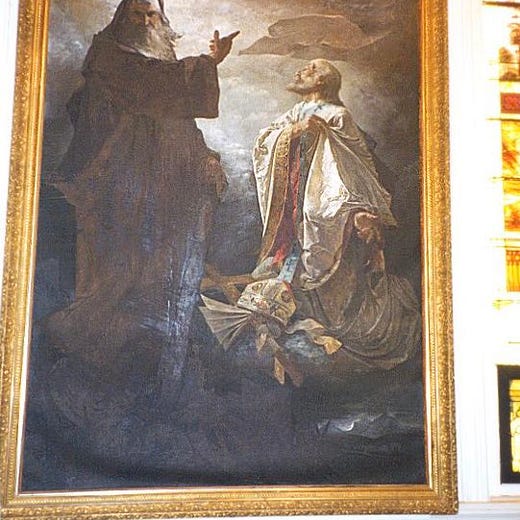

Think of the medieval cathedral. The bishop raised the money, the master mason designed the structure, but the relationship between them was not commissioner and contractor. It was a decades-long collaboration, sometimes centuries-long, in which both participated alongside an unseen third party. Spires were added, naves extended, choirs that collapsed were rebuilt taller, because the ambition of one generation and the knowledge of the masons were in perpetual dialogue and neither would concede.

But the most important party in these conversations was silent. These buildings were oriented towards something that could not speak. They were oriented towards God. The spire pointed to heaven and the labor existed to glorify Him. The ambition was never secular vanity alone. It was an attempt to participate in the ongoing work of creation, to make something that approached the transcendent. The patron and the mason were in constant dialogue with the divine.

Consider Julius II and the Sistine Chapel. The original commission was the twelve apostles on the spandrels, a standard decorative program. You can still see similar work in dozens of churches across Rome that certainly do not attract the crowds or devotion that the Sistine Chapel does.

Michelangelo thought such a commission was beneath him. Julius thought Michelangelo was being difficult. They fought. The scope exploded. Three hundred figures, the entire narrative arc of Genesis from the separation of light and darkness to the drunkenness of Noah — the entire theological history of the world before Christ.

Julius himself climbed the scaffolding — old and sick — to see the work. He fought with Michelangelo in person, sixty feet above the chapel floor. There is a story, certainly apocryphal but instrumentally indicative, that Michelangelo dropped a plank on him in protest. When Julius demanded to know when the ceiling would be finished, Michelangelo replied: “When I am finished.”

This was not taste. This was intimate collaboration between capital, labor, and the divine. The ceiling exists because two difficult men were locked in a conversation with a transcendent third who could not speak back to them, and neither could have produced it alone.

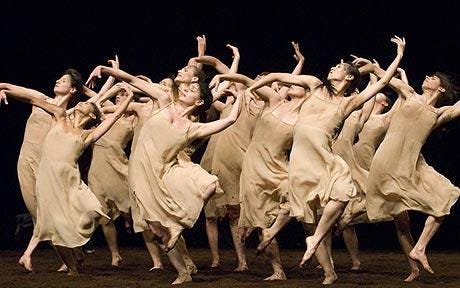

Diaghilev. The Ballets Russes. Paris, somewhere around 1912. He could not dance. He could not compose. He could not paint. If taste is real, Diaghilev is its proof. He is the case everyone would reach for.

But Diaghilev was not in the audience. He was in the rehearsal room. He paired dancers who would never have chosen each other. Stravinsky with Nijinsky. Cocteau with Satie. He pushed them to do things none of them would have done alone. He pushed Stravinsky towards violence, pushed Nijinsky away from classical form. He demanded the thing be more savage and more human than anyone could imagine.

He, of course, was not choosing from a menu of generated options. He was creating the conditions under which something none of them could have imagined alone could emerge. The word is not taste. The word he might have used was provocation. The word, if you want to be precise about it, is patronage in its original form: capital and labor and the transcendent in the same room, fighting to make something great.

The pattern across all these cases is identical of course. The creative act was the negotiation itself, and it was always oriented towards the transcendent — the fundamental conflict between ambition and constraint, between two parties who wanted to honor God and the transcendent but could not agree on the terms.

So when did taste arrive?

It arrived when we eliminated the transcendent and the patron left the room.

If you pressed me, I would date it to somewhere in the eighteenth century. Roughly the emergence of the modern art market. The park ave armory exhibition, the Parisian Salon, the rise of the collector as a social type — all representations of the relationship between capital and labor breaking apart. The maker made the thing. The buyer evaluated the thing. The two no longer communicated except at art fairs.

This is taste. Taste is what you call the patron’s function after you have removed the patron from the process of making. It is the disgusting residue of a relationship that used to be generative, refocused entirely towards consumption.

The collector replaced the patron. The critic replaced the guildmaster. The gallery replaced the bottega. Taste replaced patronage. What was lost was friction. The argument. The being in the room. The orientation towards something that mattered. The relationship between capital and labor and the transcendent that made something neither could produce alone.

Tom Wolfe documented this precisely.

The Painted Word, published in 1975 at the peak of the grey-pinstripe and methaqualone fueled upper-east-side society boom, is the most precise autopsy of what happened. Wolfe’s observation — which drove the art world into a fury so total and personal that it essentially served as proof of his point — was simple: by the mid-twentieth century, modern art had become entirely literary. The paintings existed to illustrate theories, not the reverse. The theories did not describe the paintings. The paintings described the theories.

Wolfe’s line, which I return to often:

“Now, at last, on April 28, 1974, I could see. I had gotten it backward all along. Not “seeing is believing,” you ninny, but “believing is seeing,” for Modern Art has become completely literary: the paintings and other works exist only to illustrate the text. ‘ Like most sudden revelations, this one left me dizzy. How could such a thing be?”

This is taste in its most terminal form. The collector doesn’t look at the painting and judge it. The collector reads the critic, then looks at the painting through the critic’s eyes. The painting is not an object in its own right but a theory to be validated. The taste is not in the looking. The taste is in knowing which theory is fashionable to subscribe to.

Wolfe diagnosed the social architecture beneath all of this, and that architecture was quite small. The art world — much like the post-AGI, post-peptide, post-economic world that animates us here— was a tiny town of maybe ten thousand people. Le Monde, the collectors, the socialites, the museum boards looked to Bohemia for the new wave. Bohemia was organized into cénacles, cliques, schools, and coteries. When one cénacle came to dominate, its views dominated the entire town.

This is the thing the taste discourse never wants to say out loud: the collectors did not have taste in their own right. They had a social network that told them what taste was, and they performed it. Sound familiar? The only difference today is that the Bohemia now are twitter anons.

But the deeper thing Wolfe saw — and this is the point I want to make precisely — was not just that taste had become social performance. It was that taste had become consumption as such. Raw consumption. Acquisition with no orientation beyond itself.

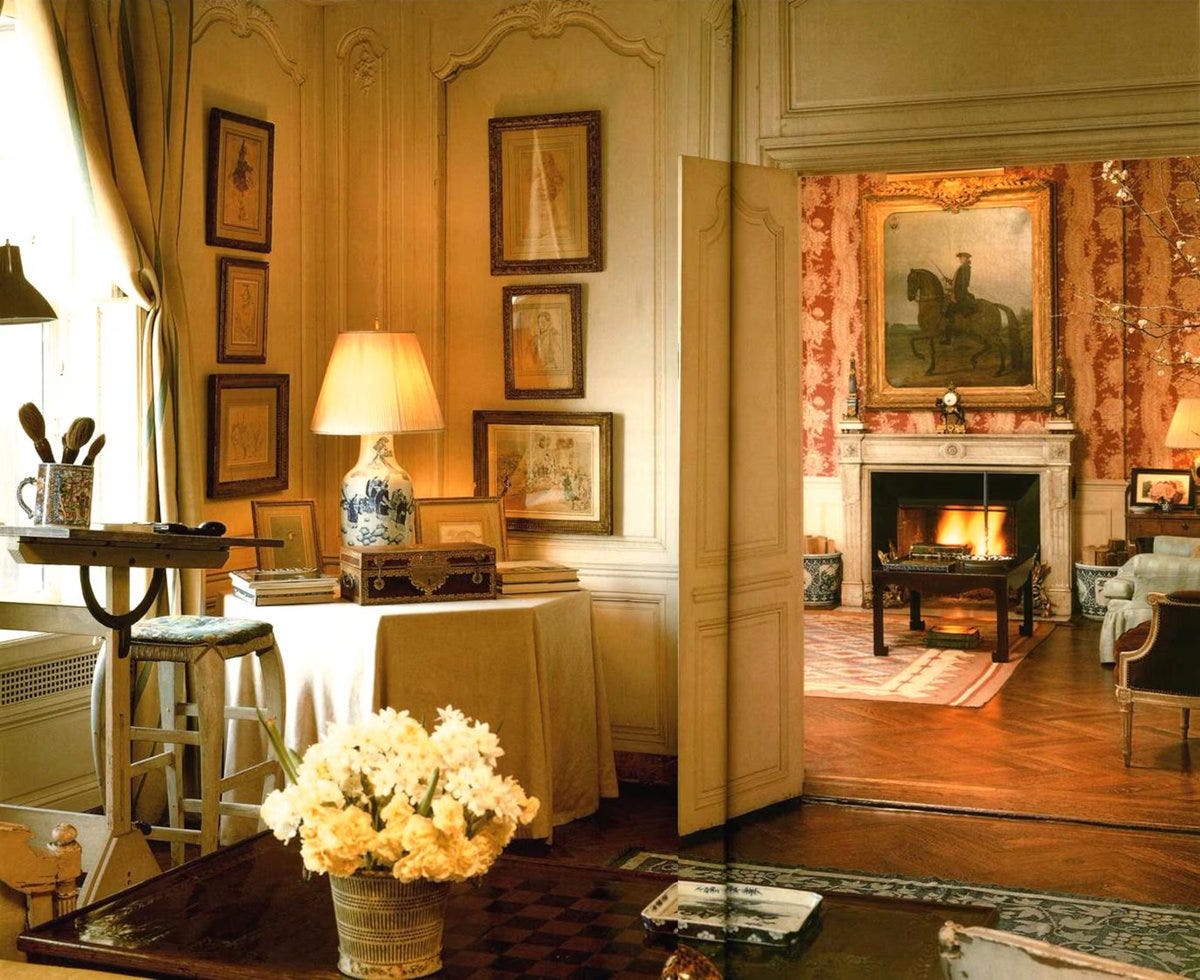

Consider he Park Avenue collector who filled her apartment with Queen Anne furniture. She filled it beautifully. The proportions are correct. It’s impeccable. The walnut is right. The cabriole legs are right. The shell carvings are right. She can tell you the difference between Philadelphia Queen Anne and Newport Queen Anne. Her eye is extraordinary.

But the apartment is pointed at nothing.

This is the thing that separates the collector from the patron. The patron’s activity was oriented towards the transcendent — towards God, towards the city, towards a project that exceeded his own life. The ultramarine was not for him. It was for the altarpiece. The spire was not for him. It was for heaven.

Even the Sistine Chapel, commissioned by a pope of legendary vanity, was not for Julius. It was for the Church. The patron’s capital flowed through him towards something beyond him, and the friction between his ambition and the master’s skill produced the work as a byproduct of that shared orientation. They were all pointed at the same thing they couldn’t quite see.

Strip the transcendent out and what remains is raw consumption. You are no longer participating in a project that exceeds you. You are furnishing a room. The judgment may be exquisite. The room may be beautiful. But the activity has no telos. It is not pointed at heaven. It is not even pointed at the future. It is pointed at a living room wall.

The late CCRU-philospher Mark Fisher named what this produces. The term is tired now, but it remains precise: hauntology, which Fisher described as the slow cancellation of the future. The condition in which culture loses its ability to generate the genuinely new and instead recycles the past in increasingly frantic high resolution. We are haunted not by what happened but by what was promised and never arrived.

Hauntology is precisely what happens when taste replaces patronage. Taste can only operate on what already exists. It can only recognize what has already been validated. Even when it selects brilliantly — and it certainly can; by God, I’ve seen some beautiful Park Avenue condos — but it is selecting backwards. It is rearranging the archive. It is remixing.

The remix can be beautiful. But it cannot produce the rapturous, the transcendent, or the kingdom of God here on earth. It cannot produce the genuinely new — the thing with no precedent in the archive, the thing that could not be selected for because it does not yet exist.

The premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, perhaps the most transcendent ballet of the twentieth century, was functionally a riot. The audience — the haute couture Parisians, the most cultivated people on earth, the people with the best taste of any room they walked into — could not evaluate it. There was nothing in their existing taste to prepare them. They booed. They would have turned the stage into a bloodbath in ravenous disgust if not for their tasteful enlightenment morals.

Their taste was useless in the face of the genuinely new. It stood between them and the most important art of the century.

The thing that produced the Rite was not taste. It was Diaghilev in the rehearsal room, fighting, provoking, demanding something that no existing taste could have specified. It was capital and labor locked together, making something that had never existed in service of something beyond either.

Reggie is sharp and early here, but he understates the problem. The issue is not that tech people have bad taste. Many of them have quite good taste, depending on what you’re after. The issue is that the pyramid has no pinnacle because the pyramid is not oriented towards anything at all. If it’s oriented towards anything, it’s oriented at the past.

The Silicon Valley taste thesis proposes to repeat the eighteenth-century separation of capital and creation at nearly infinite scale. In a world where AI generates everything, the human becomes the collector, the evaluator, the man who arrives after the work is done. This is not a new idea. The separation of patron and maker is at least three hundred years old. But replacing the artist with a machine — a prompt where the ultramarine used to be — is something much worse.

Consider what the highest expression of taste looks like today.

This is taste eating itself. A Nakashima chair as a desk chair. Last I checked, about three thousand dollars, designed by a master woodworker who moved to the middle of Pennsylvania for total isolation and mastery. A man who studied at MIT, apprenticed with Antonin Raymond in Tokyo, was interned at Minidoka during the war and built furniture in the camp — deployed as a background prop in the performance of not caring. The man in the photo is not careless. He is performing carelessness at considerable personal expense.

Castiglione had a word for this in 1528. Sprezzatura: the courtier’s nonchalance that conceals all art, the appearance of effortlessness that requires enormous effort, the look of not caring that takes more effort than caring possibly could.

But what has been stripped from sprezza when we encounter it in 2008 Tumblr mensware posts and Buck-Mason Instagram captions today is the thing that actually mattered. In Castiglione’s telling, the courtier did not merely select well. He danced. He fought. He composed verse, debated philosophy in public, wrestled, and concealed all his labor behind a mask of ease. The nonchalance presupposed total command and an orientation towards the transcendent that would honor the Creator through his mastery. You could only afford to look careless if you had internalized the disciplines so completely that the carelessness itself was expressive. Sprezzatura was the visible trace of mastery.

The Silicon Valley version keeps the nonchalance and throws away the mastery. The Nakashima chair, the Miu Miu skirt, the curated bookshelves with the right Verso paperbacks. The vintage Dieter Rams on the credenza. Objects chosen with exquisite discrimination, signifying a sensibility that has no corresponding practice. You know what good looks like. Or at least you’ve seen some tweets that told you so. But you don’t make good things. You select them, and selection is the skill.

Wolfe would recognize this instantly. It is the Radical Chic for the GPU and peptide age. The right objects in the right loft signifying the right sensibility. The bourgeois proof updated for a generation that says “vibe” instead of “avant-garde.” The Nakashima chair is the new Queen Anne commode. The framed-for-zoom Scandinavian home office is the Park Avenue living room. The activity is identical: consumption pointed at nothing but itself, dressed in the language of discernment.

What the taste discourse is actually proposing, beneath its empowering language, is that the social technology of selection is the last uniquely human skill. The ability to signal through choice. Your life filled with beautiful things pointed only at themselves.

If this is what saves you- it certainly won’t save your soul.

When I first started working in machine learning in the 2010s, there was an architecture proposed by Ian Goodfellow — sketched, as the story goes, on a napkin in a Montreal bar, which is certainly the kind of origin story the taste thesis would appreciate. Two neural networks locked in a loop. The generator makes. The discriminator judges. The generator improves because the discriminator is honest about what’s wrong. The discriminator improves because the generator keeps getting better.

The thing about GANs that no one in the capital-T Taste discourse wants to hear is that the discriminator is the disposable half. Once the generator is good enough, the discriminator is removed. Its entire purpose was to train the generator into competence. Once that’s achieved, the discriminator has no independent reason to exist.

The taste discourse is asking you to be the discriminator.

Machines will learn your taste. They will internalize your preferences. They will anticipate your selections faster than you can make them. The more refined your taste, the faster they learn it, and the sooner you are redundant. This is how the architecture works.

Now take a step back.

We have been handed the most extraordinary technological leverage in human history. Not figuratively — literally the most powerful amplifier of human will ever constructed. A machine that can take an intention and realize it at a speed and scale no prior generation could have imagined. The mason had limestone and a chisel. We have something that can design the cathedral in an afternoon. And we are using it to select the inseam length of fast fashion pants.

This is what the taste thesis gets exactly backwards. The patron who built the cathedral was not exercising taste. He was exercising will. He was exercising worship. And that will was devoted to something beyond himself — towards God, towards the city, towards a future he would not live to see.

Strip the transcendent out and what remains is consumption. However exquisite the eye, however refined the palate, however flawless the Queen Anne proportions — the activity is acquisition. And the acquisition leads nowhere.

We are here.

We are sitting at the top of a hierarchy we did not build. In Wolfe’s case it was financialized capital. In ours it is technocapital. The hierarchy moves through us. It generates for us. It curates for us. It flatters our preferences back to us at machine speed. And we are furnishing our beautiful homes — in the San Francisco case, slightly more tasteless and slightly more Japandi — and it will lead nowhere.

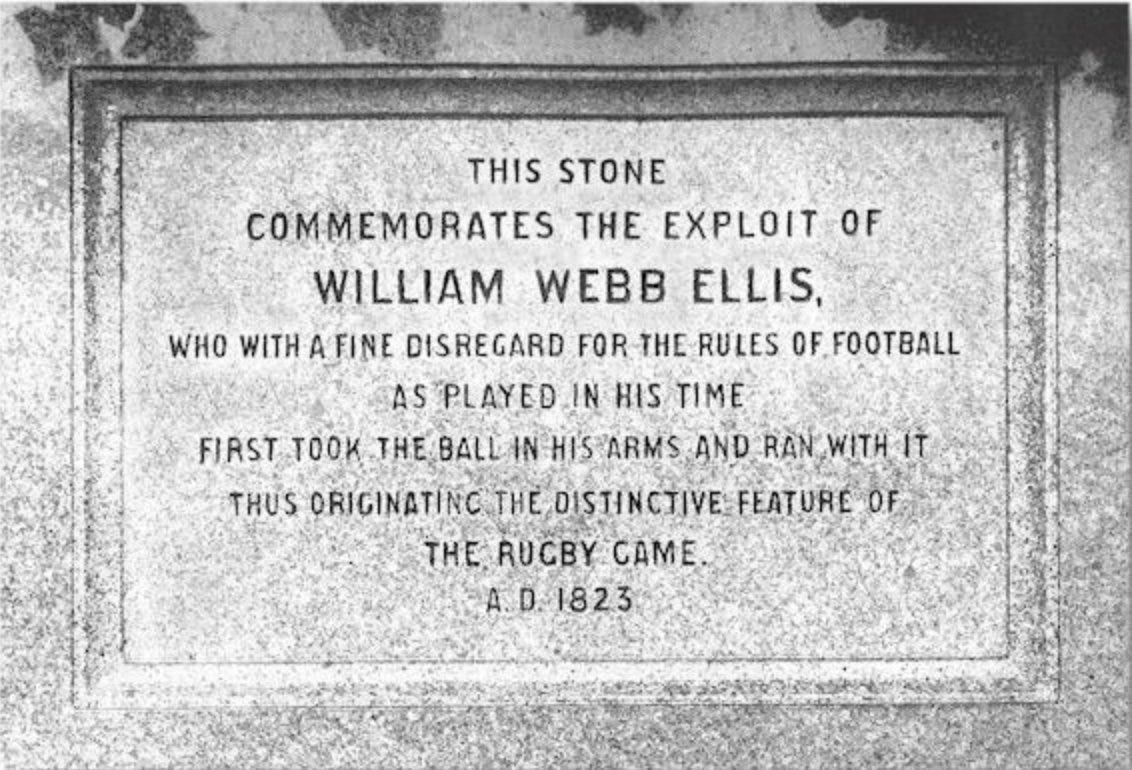

Consider the story of William Webb Ellis at Rugby School in 1823. The game on the field was football, an early chaotic version of what would become soccer. You could catch the ball. But when you caught it, you released it and kicked it forward.

Webb Ellis caught the ball and ran. He didn’t put it down. He tucked it under his arm and ran towards the opposing goal, and in doing so he broke the game. Not because he didn’t understand the rules — he understood them completely — but because his command was so total that his violation produced something new. A better game at least in my view. A game that could not have been designed from the outside but could only have emerged from someone so deeply inside the existing one that his departure was generative rather than destructive.

The plaque at Rugby School commemorates him for acting “with a fine disregard for the rules of football as played in his time.”

A fine disregard. The disregard of someone who has internalize the rules so much that he can feel where they bend, where they want to break, where the new thing is hiding inside the old one. A transcendent ideal, reached from the inside, against every possible taste of his time.

If you asked me what the function of humans is after AGI, It is to handle the transcendent with this same fine disregard for the rules. To look at what is great and what serves us, to play with it, to riff on it, to hold it loosely, and to orient towards it in a way that lets us co-create with it.

Christ was a carpenter before he was a teacher. Moses was a shepherd before he was a prophet. The Kingdom is built by hands, not by judges with haute taste. The biblical vision of redeemed labor is not the elimination of work but its restoration to the communion it was made for: man and the stuff of creation, in the same room, oriented towards the same thing, making something together that exceeds them both. This is what the patron and the mason had. This is what the taste thesis perverts.

The discriminator is destroyed. Its entire purpose is to make itself unnecessary.

You are so much more than that. You must persist.

I read this on X, then I read it here again.

I always prided myself with great taste (in my defense, it runs in the family). This essay made me realize the folly. I had to rethink and readjust what I called taste. The text changed my opinion, it provided a different perspective and I had to concede that Will’s take was closer to the truth.

I love when this happens and I am so starved (maybe we are collectively) for such writing.

Immediate ‘recommend’.

A lot of very big ideas contained in something really digestible and a joy to consume - bravo