End Game Play

It is 1985. Garry Kasparov sits across from Anatoly Karpov in Moscow. It is Game 24.

This is the second time the two men would meet. The first, the year prior, ran forty-eight games over five months before FIDE president Florencio Campomanes controversially ended it with no result. Karpov was leading 5-3 but visibly deteriorating, had lost something like twenty-five pounds, and looked like he was dying over the board. By the time Kasparov sits down for the rematch these two have been locked in a single unbroken psychological war for over a year.

The score is 12-11. Kasparov needs a draw to win.

Kasparov is twenty-two. He has spent a meaningful fraction of those years preparing openings. His choice is the Sicilian Najdorf, probably the most theoretically dense opening in chess.

His seconds—Nikitin, Dorfman, Timoshchenko—are not running simulations. There are no real chess engines in 1985. They are grandmasters in a late night hotel rooms dense with cigarette smoke and cluttered with physical boards, mining by hand for novelties and new lines.

Kasparov burns forty percent of his clock before the middlegame. This is how serious people play.

Today the median grandmaster game spends maybe five percent of thinking time on the opening. The first twenty-five, thirty moves have become recitation, blitzed at speed, both players rushing to reach the endgame.

When Magnus Carlsen abandoned the classical World Championship in 2023, the reason he gave was boredom. Elite play in modern chess means years memorizing computer lines only to show up and recite them until you reach the endgame where real play can occur.

Magnus gave the game up and moved to rapid and blitz. Both formats too fast for deep prep, where you have to actually play.

Chess has become an endgame sport. The opening and the middlegame, where you feel your way into a position, where complications arise that no one planned for, have been compressed into filler. You skip them. You rush past them. You play for the endgame.

However this is not a story about chess.

Across every domain we have stopped playing openings. We have stopped playing middlegames. The instinct everywhere is to skip directly to the endgame. To reason backward from the terminal state and treat everything between here and there as something to recite and move on.

Consider modern war. A century ago, wars were fought with openings. The first weeks of August 1914 determined the shape of the next four years: the Schlieffen Plan’s failure at the Marne locked both sides into trenches that would not move for fifty months. Eisenhower spent years on the opening of the Western Front: the selection of Normandy over Calais, the deception campaigns, the weather delays, the decision to go on June 6th despite conditions that made his meteorologists sick.

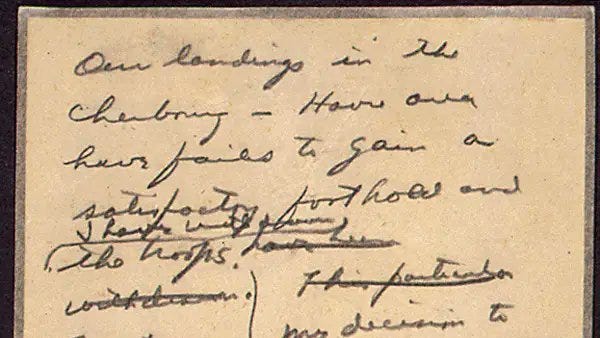

He wrote a letter taking full responsibility for the invasion’s failure and kept it in his pocket. If he got this opening wrong, a million men would have died for nothing.

The wars we fight now have no openings.

‘Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”

In Yemen we bomb buildings that are already rubble. In Iran we pretend to destroy Fordow and the Iranians pretend to believe us, then hit Al Udeid and we pretend not to notice. In Venezuela we spend months blowing up boats in the Caribbean and stage the abduction of a man while his government stays intact. These are wars not being fought, but recited. Both sides blitzing through a script to reach a foreordained position.

The middlegame did not disappear. In the Donbas there is no computer simulation. It is the Somme with drones: men dying in mud and minefields to inch a position forward that no model can solve cleanly. The trenches on the Western Front didn’t move for fifty months. The trenches in eastern Ukraine haven’t moved in three years. The middlegame is still there. It is still brutal. It is still where the actual consequences land. But our understanding of the struggle did.

The opening has been engineered out. What remains is the performance of mass consequence without the risk of it. Eisenhower’s advance today would be fought with 22 JSOC operators and some drones, not a million men at the front. The idea of opening a war, not ending one, with this narrow precision would be absurd a generation ago-- but not in an endgame world.

Endgame mentality extends far beyond the battlespace and the chess board. Consider, the recent Cheeky Pints episode with Elon Musk.

Dwarkesh Patel interviews Elon Musk and asks a middlegame question: where does the power come from to run data centers in space. How do you service GPUs that fail in orbit. What is the cost path for solar cells in thirty-six months. Positional questions.

Musk will not play the middlegame. Within seconds he has moved from the engineering of a single data center to harvesting a millionth of the Sun’s energy, to a mass driver on the Moon shooting AI satellites into deep space at two and a half kilometers per second. Dwarkesh asks how you manufacture a terawatt of chips by 2030. Musk says he’ll build a TeraFab. Dwarkesh asks how you start a chip fab when you’ve never built one. Musk says he’ll figure it out. Every time Dwarkesh tries to hold the position— what are the actual moves between here and there— Musk skips past it to the next boundary condition.

They do not disagree about the endgame. In fact, these two men are totally aligned in beliefs that would seem utterly outlandish to all but a small set of Bay Area rationalists. That is a belief that we are mere months away from a coming digital singularity that will produce self improving intelligence from raw silicon that will in turn consume 99% of the energy output of all complex civilization to date in its perpetual quest for self improvement.

Dwarkesh does not dispute that AI scales to terawatts. He does not dispute that it ends up in space. He has already conceded the terminal position. What he disputes is how much middlegame you can skip. Musk’s answer, every time, is all of it. The limiting factor is power. Solve it. The limiting factor is chips. Solve it. The limiting factor is mass to orbit. Solve it. The middlegame is not a phase to be inhabited. It is a series of bottlenecks between now and the endgame, and bottlenecks exist to be eliminated and not paid much attention to otherwise.

This is terminal endgame reasoning. And it works— at SpaceX and Tesla, in ways that are difficult to argue with. Steel instead of carbon fiber. Catching boosters on the tower. The Gigafactory. He has been right often enough that dismissing the method is not serious.

But when the conversation turns from hardware the method breaks. Dwarkesh asks what the relationship between humans and AI looks like in practice. Musk jumps past it. Humans will be less than one percent of all intelligence. The AI will either have the right values or it won’t. We are either the chimps in the protected zone or we are dead. When Dwarkesh pushes— how do you actually make Grok care about human consciousness— Musk says he’ll tell it to.

This is not a middlegame answer. This is a man who has already recited his way to move thirty and is waiting for the endgame to begin.

Endgame play is a symptom of simulation. Engines exhausted the opening and middlegame of chess so humans skip to the only phase that isn’t pre-computed. Both sides of a modern war can model the front, model the force projection, model the outcome— so the opening collapses and what gets fought is the narrow sliver simulation can’t price. Musk simulates forward from the terminal state and treats everything between here and there as bottleneck. Already computed. Already recited.

Of course he does. Our engines are better than Kasparov’s notebooks. The opening Eisenhower spent years agonizing over could have been modeled by anyone with a map and a calendar and enough compute. Simulation compresses whatever it can reach. Human effort migrates to whatever it can’t. This is how it has always worked. It will be more true after AGI than before. That is more phases of more games compressed into recitation, more human work pushed to the edges where the position is still live.

But we have made a category error. We have confused simulating an endgame with arriving at one. These are not the same thing. The ability to model the terminal state of AI does not mean the terminal state of AI is close. The ability to simulate the outcome of a war does not mean the war is over. We have become so fluent in endgame reasoning that we have mistaken fluency for proximity and proximity to the end is the only thing that makes work feel urgent anymore, so we keep manufacturing it.

God did not build a world that was immediately primed for judgment. It has been two thousand years. It will very likely be many more.

Scripture is filled with men that are faced with this same category error. Abraham died without receiving the promise, Moses never entered Canaan. Hebrews holds them up not as men who failed to reach the endgame but as men who played the middlegame so well it didn’t matter that they never reached it. They were not proximate to the end. They were nowhere near the end. The middlegame was their vocation.

We have convinced ourselves that simulation has exhausted the middle of everything— war, technology, politics, the economy— and that the only serious move left is the last one. Simulation has not exhausted the middle. It has exhausted our patience for it. The middle is still where the complications live, where the position is ambiguous and the thing no one modeled happens and you have to play the board as it is. The middle is two thousand years long and counting and we are somewhere in it and the eschaton is not ours alone to force.

Know your vocation. Play the game. Burn the clock.

“Play the game. Burn the clock.” is a beautiful conclusion.

I wonder how much game theory studies would impact / self-correct this distortion., and how much of end game play is just intellectual laziness.

I see this extended everywhere. I talked to a climate scientist recently and their answer to everything was 'ban fossil fuel usage', and every question that I had about how was skipped over and taken straight to endgame. It really contributes to political and idealogical polarization, I think. The details and the feasible practicalities have a way of normalizing polar ideas to a realistic middle ground.