Rented Virtue

Will Manidis & Nabeel S. Qureshi

The Forge

In January of 1709, in a steep gorge cut by the river Severn in the midlands of England, a 30-year-old Quaker named Abraham Darby fired a blast furnace for the first time.

The furnace had been built decades earlier and blown up around 1703 by a previous operator. It sat derelict in the Coalbrookdale Valley, where coal and iron ore lay in abundance near the surface of the valley walls, and a narrow stream cut through the bottom with enough force to drive a water wheel and bellows. Darby had leased the wreck in September of 1708, the year prior, and spent a few months rebuilding it.

As a boy in the 1690s, Darby had been an apprentice to Jonathan Freeth, a fellow Quaker who made malt mills. Darby understood from watching men brew ale that you did not smelt with coal, and if you smelt it with coke by baking out the sulfur first, you could produce a high quality product. The coal in the Coalbrookdale Valley happened to be unusually pure, and when you burned it, it yielded fuel clean enough to produce castable iron.

On the 10th of January, he had his first blast day. Fully liquid high-quality iron flowed into the molds. Little did he know that with his firing, he had lit the fuse of the Industrial Revolution.

It is difficult to overstate the problem that Darby solved. Before Darby, iron production in England was structurally capped. Every furnace could only be run on charcoal, and charcoal required timber. England, with its relatively small land area and low-density forests, was running out of trees. Iron masters competed with ship builders and construction for a shrinking stock of wood, and furnaces sat idle for months, waiting for enough fuel to turn them on. The industry had been in structural decline for over a century.

Darby’s invention would set Britain up to become the greatest empire in history. Every partnership that fueled this first forge was Quaker. Thomas Goldney of Bristol financed the works. Richard Ford, also a Friend, married Darby’s daughter and managed operations. When Darby offered to teach his smelting technique to another iron master, the man he chose was William Rawlinson, a fellow Quaker. Weekday meetings were held in the company offices at the works. On Sundays, Darby sat with his fellow workers at a Quaker meeting in the town nearby.

When he died in 1717, only 39 years old, and his widow died just months later, his eldest son was six. The business should have collapsed and Darby’s invention should have been lost to the wind. Instead, Joshua Sergeant, Darby’s brother-in-law, bought back the mortgage shares on behalf of his children, and Ford held the enterprise together until the boy was old enough to take his place. The Quaker network absorbed the loss through a mutual obligation they felt towards each other and to the enterprise. Their shared faith and the long patience of people who believed their work participated in something that would outlast them fueled resilience for the business.

Abraham II expanded the works, introduced steam power, and paid higher wages than the local mines. And in times of food shortage, he bought farms to feed his workers. When he died in 1763, his son Abraham III took control at 18. In 1779, he completed the Iron Bridge over the Severn, the first cast iron bridge in the world,100 feet across. Nearly 400 tons of iron cast in the family’s furnace went into its construction. He bore the cost overruns personally and died in debt at 39, the same age as his grandfather. He was buried in the Quaker burial ground at Coalbrookdale.

The Barclays, the Lloyds, the Cadburys, the Rowntrees, the Clarks, and the Wedgwoods were all prominent Quaker merchant families. A religious minority that at its peak numbered almost 60,000 people in the country of 6 million – just under 1% – at that time produced an overwhelming share of England’s commercial and industrial infrastructure, so disproportionate that it still puzzles economic historians.

The standard explanation is that the Test Acts barred Quakers from universities and public offices, so they moved their talents into trade. That is likely true, but also insufficient. Plenty of persecuted minorities channeled their talents into trade. Most of them did not build Barclays. The question of why the Quakers so radically changed Britain and, in turn, the economic history of the West is worth answering.

2. On Quakers

Quakers are a strange people. I, Will, should know. I grew up as one. They’re a sect that refused to swear oaths, refused to remove their hats before magistrates, refused to address anyone with honorifics, and finally refused, with a stubbornness that cost them dearly in fines, imprisonment, and social exile, to lie. Not in the way that most religious communities refuse to lie, which is to say they aspired to it one day and often fell short. The Quakers earnestly enforced a near-militant allegiance to the truth. Through meetings, through discipline, through expulsion, a friend who cheated a customer or misrepresented a product faced not only civil liability but spiritual reckoning before his entire community.

Everyone knew this, and everyone could trade with them safely as a result. You could trade with a Quaker even across the ocean with minimal contracts because the contract was already written in something more binding than paper: a spiritual agreement. In a place like early England where transaction costs – entire apparatus of verification, enforcement, legal recourse – were extremely high, and which in turn made long-distance commerce expensive and slow, the Quakers were able to drive that cost to nearly zero.

Quakers and Baptists were small minority communities at the time, Lutherans actually had majority regions and New England was still Congregationalist

The trust was inherited by the faith and carried into every transaction before the partners even met. Even things like fixed pricing were a Quaker invention. Before Quakers, commerce meant haggling. Every transaction consisted of a negotiation and every price was a contest. Quaker shopkeepers posted a single price and held it. You paid what everyone else paid. And you never worried about being cheated because the man behind the counter believed that cheating was a mortal sin, not in the casual way that most people believe in sins, but in the way where he ordered and structured his entire community and his life such that he could remain true to his word. Customers came in enormous numbers. Of course they did.

Quakers also refused ostentatious behavior and conspicuous consumption. Quakers did not display wealth because display was vanity and vanity was a sin. What other businessmen extracted to furnish lavish estates and carriages and display the visible performance of success, Quakers treated as excess cash flows to reinvest in their businesses. They built for the long term because they understood their work to be stewardship, a core Quaker value. The businesses existed to participate in God’s purpose.

These constraints, the honesty, the simplicity, the refusal of ostentation, the reinvestment and the fixed pricing, were a structural advantage for Quaker businessmen. Every single one of them felt like a limitation, but every single one of them was actually a moat. The religion worked something like a business strategy, but they would never call it one. The moment it became one, it stopped working.

The Quakers did not calculate that honesty was profitable and practice it; they practiced it because God demanded it, and profitability was a consequence that was beside the point, not one they could manufacture by seeking.

3. The Invisible Hand

The Quakers understood something about commerce that we have since forgotten. This is something that Adam Smith understood too. Smith today is largely remembered as an economist, but he held the chair of moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow from 1752 to 1764. His wide-sweeping lectures covered theology, ethics, jurisprudence, political economy in that order, because that was the order in which he believed they mattered.

The problem at the center of Smith’s work was first and foremost moral, not economic: how do human beings, who are selfish, form moral judgments at all? How does a creature driven by self-interest develop a conscience? His answer was the impartial spectator, an imagined observer from whose eyes we learn to judge our own conduct.

Smith was a prolific writer during his lifetime. He wrote the lectures on jurisprudence, the essays on philosophical subjects, various volumes of correspondence, and of course the famous On the Wealth of Nations, but at least in our opinion, and seemingly his own, his life’s work was The Theory of Moral Sentiments. He revised it across nearly six editions over three decades, and he was still revising it in the final year of his life, adding an entirely new section on the corruption of moral sentiments by wealth and status, a section that reads like a man who has watched his other book be fundamentally misunderstood and is trying to correct the record before he dies. He had barely touched The Wealth of Nations after its first publication, and on his deathbed he ordered 16 volumes of unpublished manuscripts to be burnt. He certainly ordered The Theory of Moral Sentiments to be protected.

I think people only took parts of his work. His 1st book, Theory of Moral Sentiments, was most important for him. There he stresses humans are intelligent, empathetic beings who aren’t or shouldn’t be selfish, and that works in our interests as humans

The Wealth of Nations is an application of The Theory of Moral Sentiments to commercial life, not the other way around. Smith understood markets as moral formation. Commerce trains morals because exchange requires it. It teaches honesty because your counterpart will not come back if you cheat him. It punishes fraud over the long run, even if it rewards it short-term. It forces repeated dealings with strangers over years, building a habit of fairness that no contract could possibly ever compel.

But Smith was deeply suspicious of merchants in their own right. The Wealth of Nations warns that businessmen will conspire against public interest at every opportunity, and that the division of labor renders workers stupid if unchecked and that employers will always collude to suppress wages. He did not believe that markets alone, left to themselves, would produce good outcomes. He believed that markets populated by morally formed people devout in their faith, operating within communities of mutual accountability, tended towards good outcomes.

He assumed of his readers that they were fully formed in Christian ethics before they even entered the market. Formed by the church, by families, by guilds, and by the dense web of obligation and expectation that life in Scotland in the 18th century made inescapable. The market rewarded the qualities of Christian life: sympathy, honesty, and the capacity to think long beyond your own life. And in this way it cultivated something much deeper and older.

When economics professionalized in 19th century America, it took with it what it could formalize and left the rest. Supply and demand, the division of labor, comparative advantage, pricing mechanisms, all made secular and atheistic. The impartial spectator was left behind. Smith became the patron saint of self-interest, and the book that he deeply cared about and spent his life on became a curiosity for weird Christian Twitter users and economics grad students.

4. The Worship of Art

Wallace Stevens turned down a tenured position at Harvard after winning the pulitzer to keep his insurance job. There’s an argument to be made that the arts, like the humanities and politics, were never meant to be done in isolation from the worldly. x.com/nabeelqu/statu…

Tom Wolfe’s 1984 essay, “The Worship of Art”, explains what happened next. Sometime in the 20th century, when businessmen lost these moral frameworks, they replaced them with art and cultural philanthropy, which became a substitute faith. The museum board was the congregation, the gala was the liturgy, and the naming rights to the hospital were a tithe. Wolfe called these Boy Scout badges. The badge did not ask questions of how you earned it, provided that you could afford it.

When you lose the framework that ties your daily work to a moral account of the universe, that void does not stay empty. Something else fills the house. The finance industry of the 1980s and the 1990s built a culture that was actively hostile to answering this question. Leveraged buyouts hollowed out towns, mortgage products extracted maximum value from people who could not understand them. Compensation structures rewarded quarterly execution instead of decades-long stewardship. The people doing the work were produced by institutions that had systematically selected against the instinct to ask whether the work itself was good.

It’s easy to call this hypocrisy, but it’s not. Hypocrisy is knowing the right thing and choosing the wrong one. This is worse and more interesting. It is a culture that has eliminated the language for asking the question at all. Harvard, Goldman Sachs, McKinsey: secular confirmation rites. They signaled membership among the elect in the way that baptism once did. Except that baptism imposed obligations, and Goldman imposed none that touched the conscience.

The form of worship is preserved but the transcendence is gone.

Robert Jackall spent years inside American corporations in the 1980s conducting ethnographic field work. He documented it in Moral Mazes, the most devastating portrait of organizational moral life ever written. A former Vice President at a major US corporation told him:

“What is right in the corporation is not what is right in a man’s home or in his church. What is right in the corporation is what the guy above you wants from you. That is the morality of the corporation.”

Jackall found this everywhere, not as a failure of the system but as the system working exactly as it was designed. Managers learn within months to read political signals with the sensitivity of an augur reading the flight of birds. They learn to never associate themselves with a project that might fail. They learn above all to never stake a career on a moral claim because a moral claim cannot be hedged, cannot be walked back, and cannot be reframed as commercially convenient. A manager who raises an ethical concern is not celebrated for his conscience. He is noted as a person who makes things complicated.

The managers Jackall profiles are not bad people. They are ordinary, often thoughtful, and sometimes genuinely principled people who operate inside structures that make the exercise of personal moral judgment functionally impossible. The structure does not feed on bad people. It produces bad behavior from good ones. So they buy their morality elsewhere — the museum board, the annual letter, the philanthropy — not because they are hypocrites but because the system has made the alternative unavailable.

Attributes that determine success in a corporate environment, from Moral Mazes: The World of Corporate Managers:

We are building the same apparatus for the technology industry. We have built an attention economy optimized for engagement metrics that make people measurably worse and we have not responded by asking whether the work is good but instead by coming up with complex, eschatological reasons why it is okay. We are building AI systems that will reshape how billions of people work, relate and think. The conversation about these systems has been cordoned off into ethics boards and AI safety teams that function as the new museum boards — asking cosmic questions that permit the real work to continue unexamined.

The Quakers could not leave. That was the instrumental difference. The Quaker merchant who cheated a customer faced his meeting and his community. The work was the test and there was no badge that substituted for it.

5. Expected Value

Effective altruism is perhaps the most expensive and intellectually sophisticated Boy Scout badge ever produced. EA was the apex of purchased virtue, a religion so rigorously constructed that it convinced an entire generation of smart and secular people that they could calculate their way to moral seriousness without ever touching the formations. You don’t need to be changed by your morals, you just need to sum the numbers correctly.

The promise was moral clarity through quantification. Maximize expected value, identify the most cost-effective charity through rigorous analysis, donate accordingly, measure impact per dollar. The framework was beautiful in the way that mathematical and formal systems are beautiful. It attracted exactly the people you would expect: quantifiably gifted, analytically rigorous, often young, often from elite technical institutions, and often deeply sincere in their desire to do good — almost uniformly unformed by any moral tradition thick enough to make them question its premises.

EA had, and still has, quasi-religious features: a clear doctrine, demanding standards, a community of believers with shared language and shared institutions, apocalyptic urgency through existential risk and longtermism. It has everything that a religion has, except for the one thing that makes religion work: it forms you through practice and through community and through discipline over a lifetime and does not let you leave when it becomes costly.

Sam Bankman-Fried’s reasoning that risking billions in customer deposits was justified if it raised the possibility of preventing existential catastrophe by even a fraction of a fraction of a percent was not a betrayal of the framework but a faithful application of it. This is the point and it is the only point that matters about FTX in the context of moral formation.

In his conversation with Tyler Cowen in April of 2022, months before the collapse, SBF endorsed expected value reasoning that would justify essentially any gamble if the stakes were large enough. After the collapse in his messages to Kelsey Piper at Vox, his immediate concern was not the customers who lost their money. It was that the scandal would make things harder for people trying to do good. The framework was so thoroughly intact that even after it produced a monumental catastrophe, he could only evaluate the catastrophe from within it.

EA manufactured a secular eschatology. Longtermism provided the structure: millennial time frames, civilizational stakes, and the possibility that actions taken now could determine the fates of trillions of people. This is a substitution for the eschaton, the final judgment and the world to come. It serves the same psychological function and provides the same sense of cosmic importance that human beings require to sustain sacrifice over time.

The problem with this manufactured eschatology is that it has two dial settings and no stable middle. It either burns too hot, producing the manic urgency that convinced SBF and others that the stakes were so high that ordinary morality was a luxury that they could not afford. Or it burns out entirely when the catastrophe remains abstract year after year after year and the daily sacrifices start to feel arbitrary. Religious traditions solve this problem over centuries through ritual, through community, through liturgical calendars that modulate the intensity of faith and practice across seasons, through narrative structures that sustain commitment across generations without requiring constant threat of judgment. These are technologies of moral formation that are extraordinarily difficult to build de novo.

6. There Is No Secular Alternative.

It’s fashionable now amongst the wealthy jet set of technologists to call for new aesthetics. Better buildings, better cities, better objects. Beautiful people occupying beautiful spaces. Powered by a new secular identity of post-scarcity and peptide maximalism. This conversation has been running for years in the progress studies community, but has recently reached the mainstream with very important and successful entrepreneurs endorsing it. Patrick Collison built Stripe Press partly around it. Marc Andreessen’s “Time to Build” gestured at it. The rationalist community, which seemingly has opinions on everything other than its own morality, has extensive opinions about it. Why is everything ugly? Why are our cities hideous? Why does nothing we build anymore have the quality that old things have? Why can we not make beautiful things anymore?

They are asking the right questions, but they are wrong about what the question is. The call for a new aesthetic is necessarily a call for a new transcendent morality. You cannot build beautiful things without beautiful and transcendent reasons for making them.

Christopher Alexander understood this and nearly destroyed his career. He spent decades producing A Pattern Language, a book that is impossible to miss on the shelf of nearly every Silicon Valley elite. Probably the most important influential work on architecture and design. Software engineers love it. It is ultimately a seemingly secular book. It is a book about patterns. There are 253 of them, rigorously documented, covering everything from the distribution of towns to the placement of windows. It is a magnificent achievement of systemic thinking applied to the built environment.

However, Alexander came away believing it was fundamentally incomplete. He spent the last decades of his life on a book called The Nature of Order. Four volumes published between 2002 and 2004 that almost no one has read. In fact, the book is almost impossible to find in print today while A Pattern Language is seemingly everywhere. The question that drove these volumes was simple and unanswerable in his existing framework. Why do some things feel alive and others do not? Why does a courtyard in Andalusia feel alive but an office park in South San Francisco does not? A medieval village in Tuscany feels alive, but a new city built by technologists in California does not.

The difference is not reducible to geometry. It is certainly not reducible to a pattern. Alexander – a trained mathematician – tried. He spent 20 years trying to find a formula for it, and he couldn’t get there. Instead:

“I try to find in my own experience what it is that I feel to be holy. I have come to believe that the ultimate effort of a serious artist or a serious builder is directed towards something with the presence of God.”

The man who wrote the most rigorously systemic and material book on design in the 20th century spent his final years arguing that the quality he had been trying to formalize was not an aesthetic or material property at all. It was a theological one. Good making, good building, good design participates in something transcendent. It was the aliveness he could feel in a courtyard in Seville and not feel in a strip mall in the Tenderloin. He could not explain the beauty without the God that underlay it. The patterns were real but necessarily insufficient.

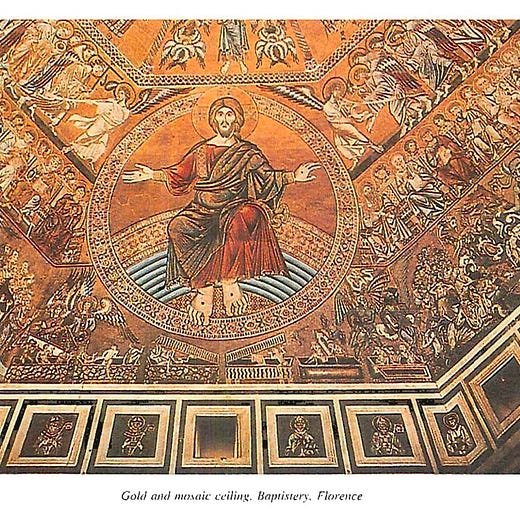

This is obvious to anyone that has ever participated in a faith tradition. No purely secular building has approached the beauty of the old cathedrals. No secular music has ever reached Bach. No secular poetry has touched the Psalms.

The craftsmen who built churches worked for decades on stone carvings placed so high that no human eye would ever see them clearly. They carved them anyway. They carved for God. Those calling for new aesthetics without calling for the thing that has always produced great aesthetics are asking for the fruit without the root.

One of our favorite writers, Dorothy Sayers, is remembered, when she is remembered at all, as a mystery novelist. She wrote the Lord Peter Wimsey detective stories in the 1920s and 1930s and they were very popular and very good at the time and are largely forgotten in our own. What is also largely forgotten is that Sayers was one of the sharpest theological minds in wartime Britain, a close friend and intellectual peer of C.S. Lewis, and one of the first women to receive a degree from Oxford. In 1942, in the middle of the war, she delivered an essay called “Why Work?” to a gathering in Eastbourne, just a few hundred miles south of where that first blast furnace was lit. We believe it to be one of the most important things written about labor in the twentieth century and almost no one has read it.

Her argument was that the church had catastrophically failed the working person by treating work as merely instrumental — a way to earn money for living and giving rather than as something sacred in its own right. The church told the carpenter not to drink and to come to services on Sunday. It never told him that the quality of his carpentry was itself the religious act. Sayers thought this was a disaster and said so:

“The church’s approach to an intelligent carpenter is usually confined to exhorting him not to be drunk and disorderly in his leisure hours, and to come to church on Sundays. What the church should be telling him is this: that the very first demand that his religion makes upon him is that he should make good tables.”

The work, for Sayers, was prayer. The shoemaker makes good shoes because that is what shoemakers do, because the object leaving his hands will either participate in the work of glorifying creation or degrade it. Christ was a carpenter. Moses was a shepherd. Paul made tents.

The AI megacycle that will unfold over the next ten years will produce more overcapitalized businesses searching for an identity than any boom in history. The temptation will be to purchase virtue. Fund the institute. Publish the hand-wringing annual letter that might even include a Bible verse or two. The actual work will remain untouched by any of it.

Every secular constraint eventually faces the question: why maintain this when it is costly? The only thing that has ever held a constraint in place across generations, through pressure, through loss, through the slow grinding temptation of day after day to simply stop, is the conviction that the constraint was not chosen but received. That it comes from something outside the self that the self cannot renegotiate. That it is owed to God and to creation itself.

The businesses that lasted understood this. Each of them had something at the core that looked, to outside eyes, like irrationality. A refusal that made no sense. A constraint held well past the point where a rational person would have abandoned it. If you asked why the constraint was there, and kept asking, you arrived at God. You always arrived at God.

The work that lasts from this era will be no different. The companies that endure, the technologies that serve rather than consume, the institutions that hold their shape across generations when the founders are dead and the capital is restless and the market is telling them to be something other than what they are — they will have something at their center that resists justification in purely secular terms. Something that seems religious, because it is.

There is no secular alternative. There has never been one.

Absolutely sublime piece. Thanks so much for writing and sharing this.

What about faith, secularism and adherence to the ethical principles of the Ten Commandment